Science Focus

Neutron Stars and Pulsar Timing

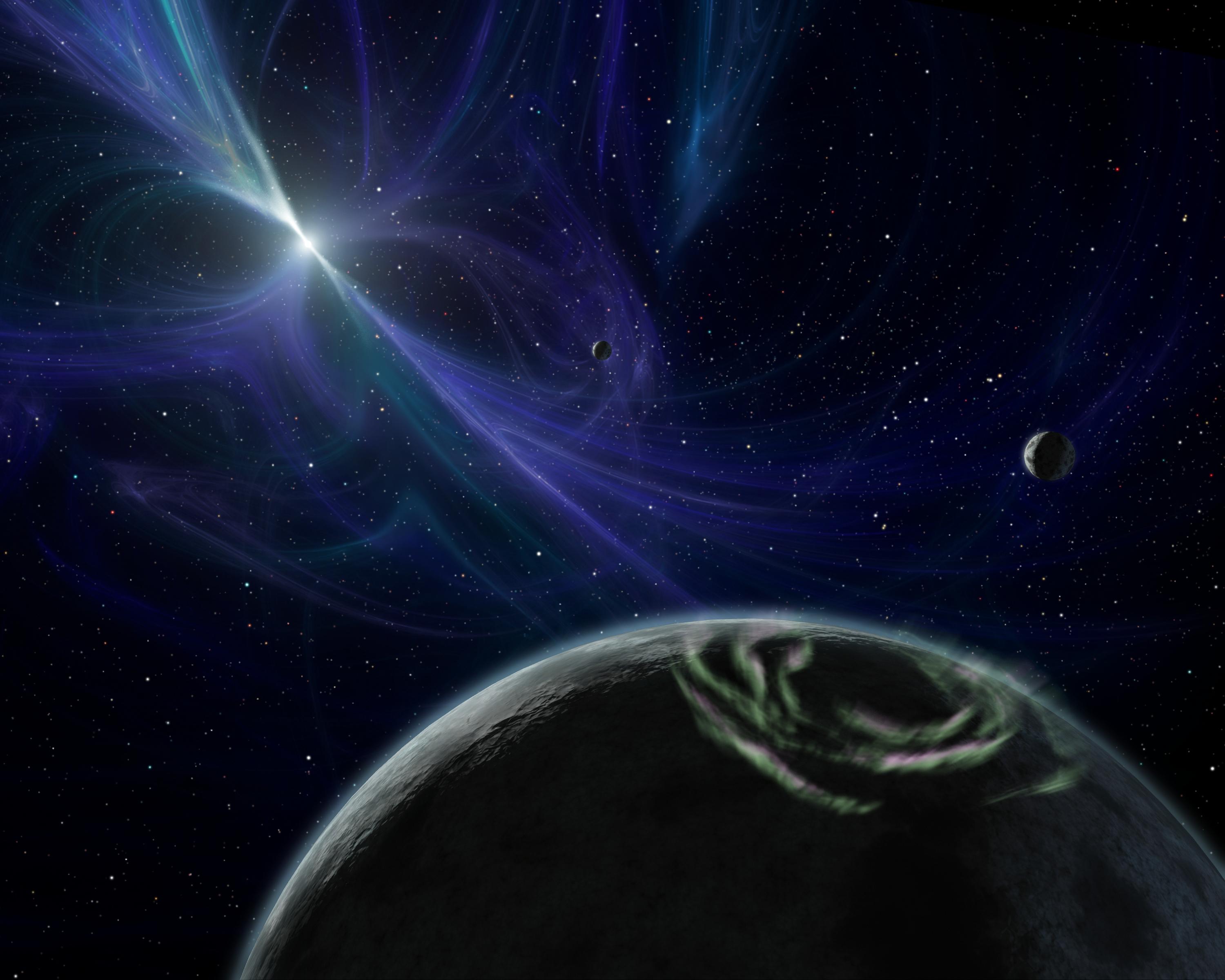

Stars with that have masses greater than about 8 times that of our Sun will end their lives in core-collapse supernovae. One of the potential remnants of these explosions is a neutron star, incredibly dense and compact objects host to extremely strong magnetic and gravitational fields. Some spinning neutron stars have be observed to emit beams of electromagnetic radiation from along their magnetic poles which we observe as periodic flashes of light. These neutron stars are referred to as pulsars

By precisely measuring the arrival time of these light pulses we can learn a swath of information about the properties of pulsars, attempt to detect gravitational waves originating from supermassive black holes, and undertake the some of the most precise tests of General Relativity.

Some pulsars have been observed to undergo sudden spin-up events, resulting in deviations in their measured pulse arrival times. These "glitches" in the pulsar spin are thought to arise either from a star-quake in the neutron star crust, or from coupling between the crust and superfluid interior of the star. Measurements of these glitches allow us to probe how matter behaves at the ultra-high densities that exist inside neutron stars.

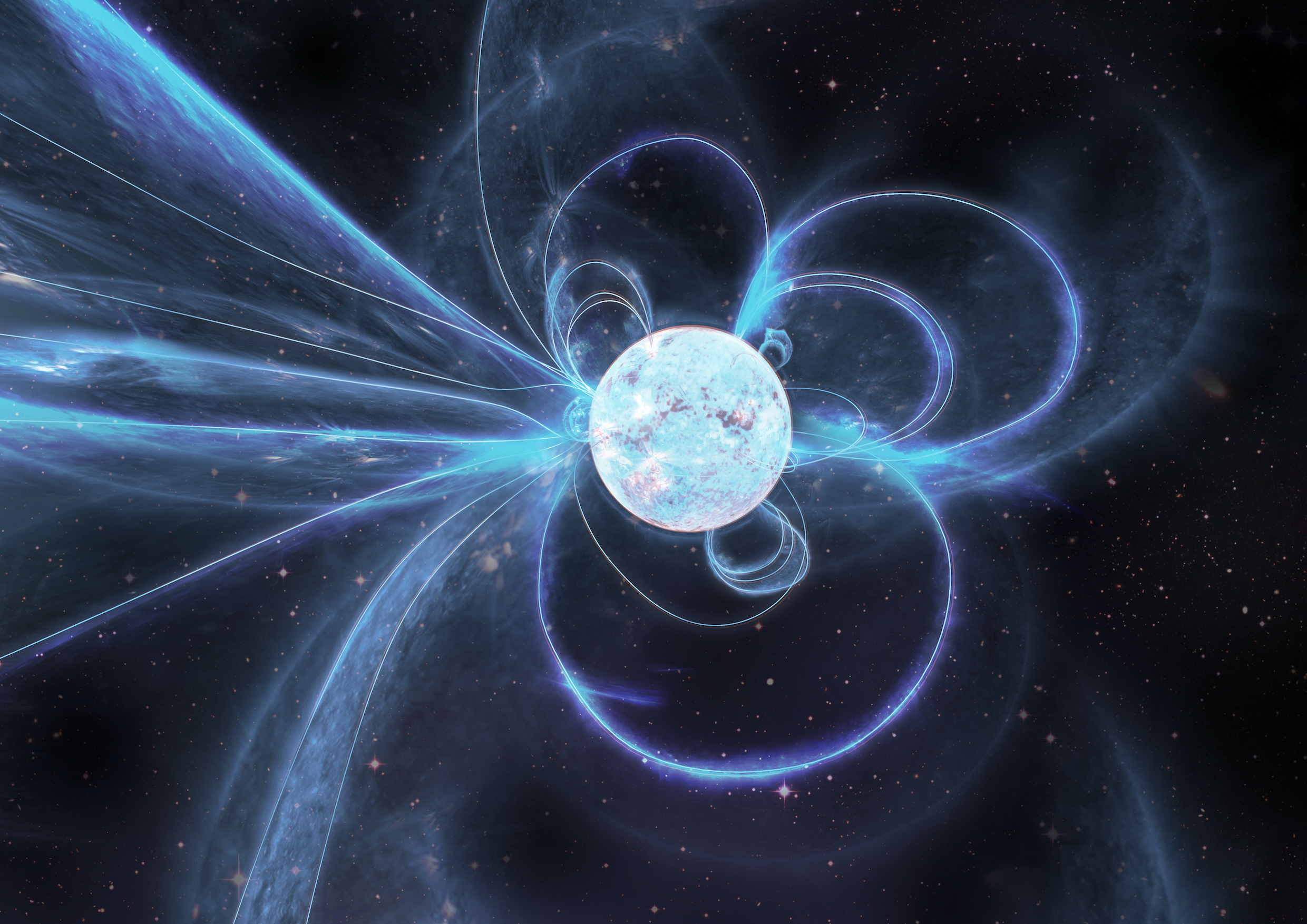

Magnetars

Magnetars are a class of slowly rotating neutron stars which posses the most powerful magnetic fields in the known universe. Many of these objects have been observed to emit extremely energetic x-ray and gamma-ray bursts. Of the 24 known magentars (see: the McGill magnetar catalogue), we have only ever observed 5 that emit pulsed radio emission similar to pulsars. These "radio loud" magnetars display large variations in their brightness and rotational stability over times, in addition to emitting remarkable millisecond-in-width spikes in their single-pulses.

Binary Black Holes

The first ever direct detection of gravitational waves by Advanced LIGO originated from the merger of two massive black holes. While the physics behind how individual black holes form is well understood, it is completely unknown how the binary black holes we have observed ended up in binaries. Measurements of the orbital eccentricity of binary black holes can be used as a method for distinguishing different formation channels. Different formation mechanisms result in varying distributions of orbital eccentricities, as the physical processes behind them can lead to vastly different initial binary conditions.

Observing Projects and Proposals

I am involved with a number of ongoing reserach proposals which utilise the CSIRO Parkes Radio Telescope in Australia, and the MeerKAT array in South Africa. Listed below are a few of the projects which I am currently contributing to.

Understanding the Remarkable Behaviour of Radio Magnetars

I joined this project in late 2018, just before the radio revival of XTE J1810-197. As the primary magnetar observation project at Parkes, we monitor the polarisation, flux and rotation of three out of four known radio bright magnetars: 1E 1547.0-5408, PSR J1622-4950 and XTE J1810-197. Our observations provide a window into the remarkably dynamic magnetospheres of magnetars, which could allow us to place constraints on the origin of their radio emission.

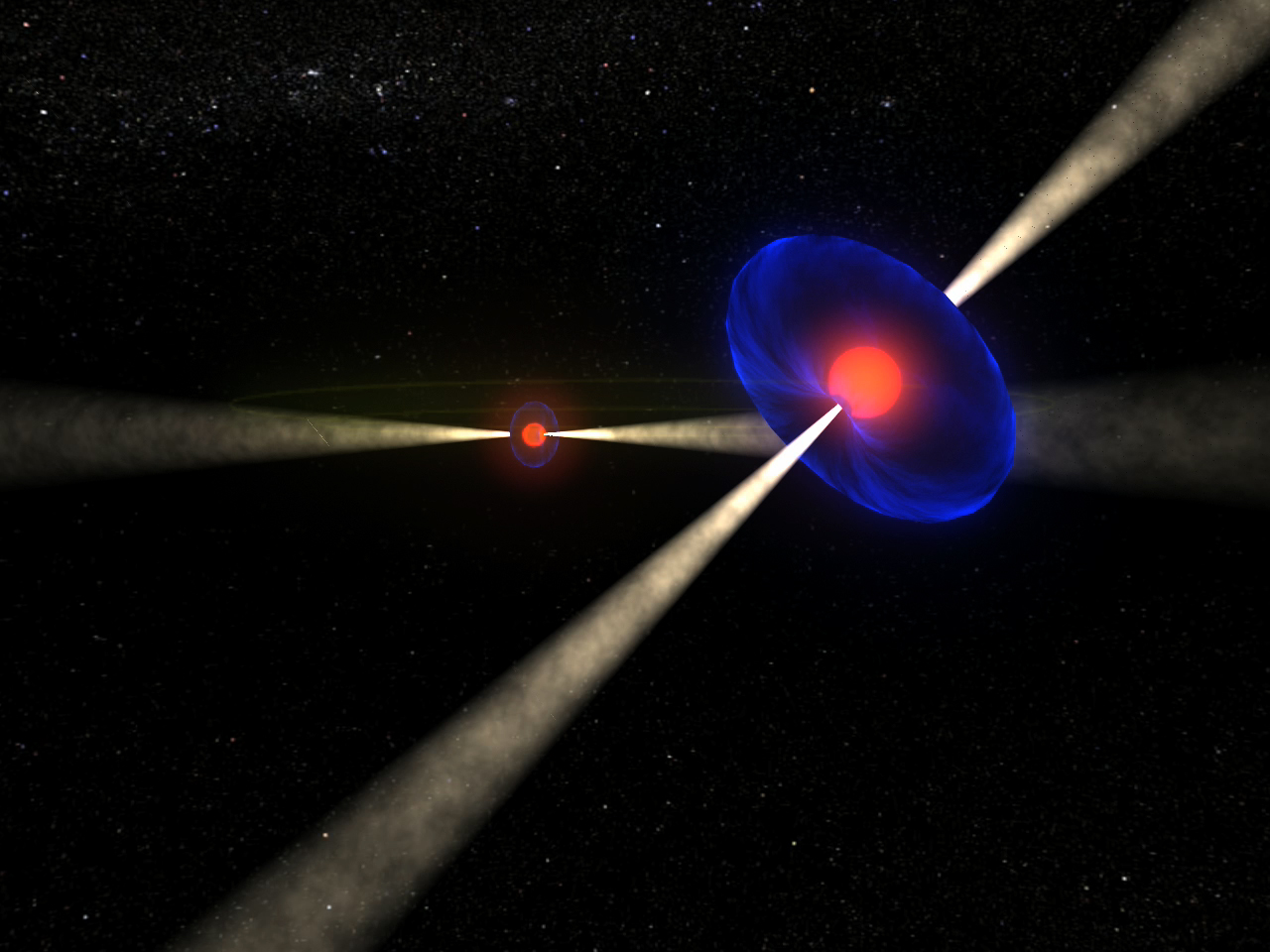

Mass Measurements of Southern Binary Pulsar Systems

This is a proposal to use the recently comissioned Ultra Wideband Low receiever of the Parkes Radio Telescope to perform timing measurements of 11 southern pulsars which have compact object companions. Combining the Parkes data with ultra-high precision observations from MeerKAT may allow us to accurately measure the pulsar and companion object masses. This can be done by observing the General Relativistic delays in the arrival time of the pulsar's radio pulses.

Magnetospheric eclipses of the Double Pulsar

I am the lead co-investigator of two projects that use the extreme sensitivity of MeerKAT to analyse the eclipses of PSR J0737-3039A by its companion, PSR J0737-3039B. These projects aim to directly probe the magnetosphere of J0737-3039B in unprecedented detail, and place stronger constraints on General Relativity.